Gulf of Maine Warming

Rising ocean temperatures in the Gulf of Maine is one of the greatest concerns for the future of New England’s Atlantic cod fishery. While overfishing in the last 60 years has depleted the Gulf of Maine’s cod population, ocean warming over the last five years has contributed to cod’s inability to bounce back, despite the strict fishing regulations that have been put in place. Cod fishing quotas are being set lower and lower due to repeated underestimation of the negative impact warmer water temperature has on cod behavior and fecundity. There are two main sources of warming in the Gulf of Maine.

The first is the general warming of the world’s oceans from global warming. Scientists suspect that the world’s oceans act like a buffer to global warming, absorbing the heat trapped in the atmosphere by increasing levels of greenhouse gasses. Oceanic data collected by NOAA shows that global ocean temperatures have been increasing at an average of .13 degrees Fahrenheit per decade since 1901, with current temperatures about a full degree higher than a century ago.

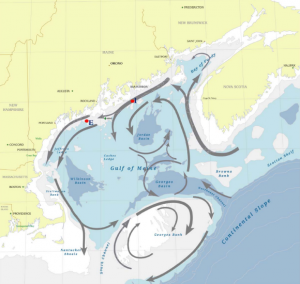

Cold water from the Labrador Current enters the GOM from the northeast Atlantic, circles counter-clockwise around the Gulf, and then exits out through the South and Northeast Channels around Georges Bank.

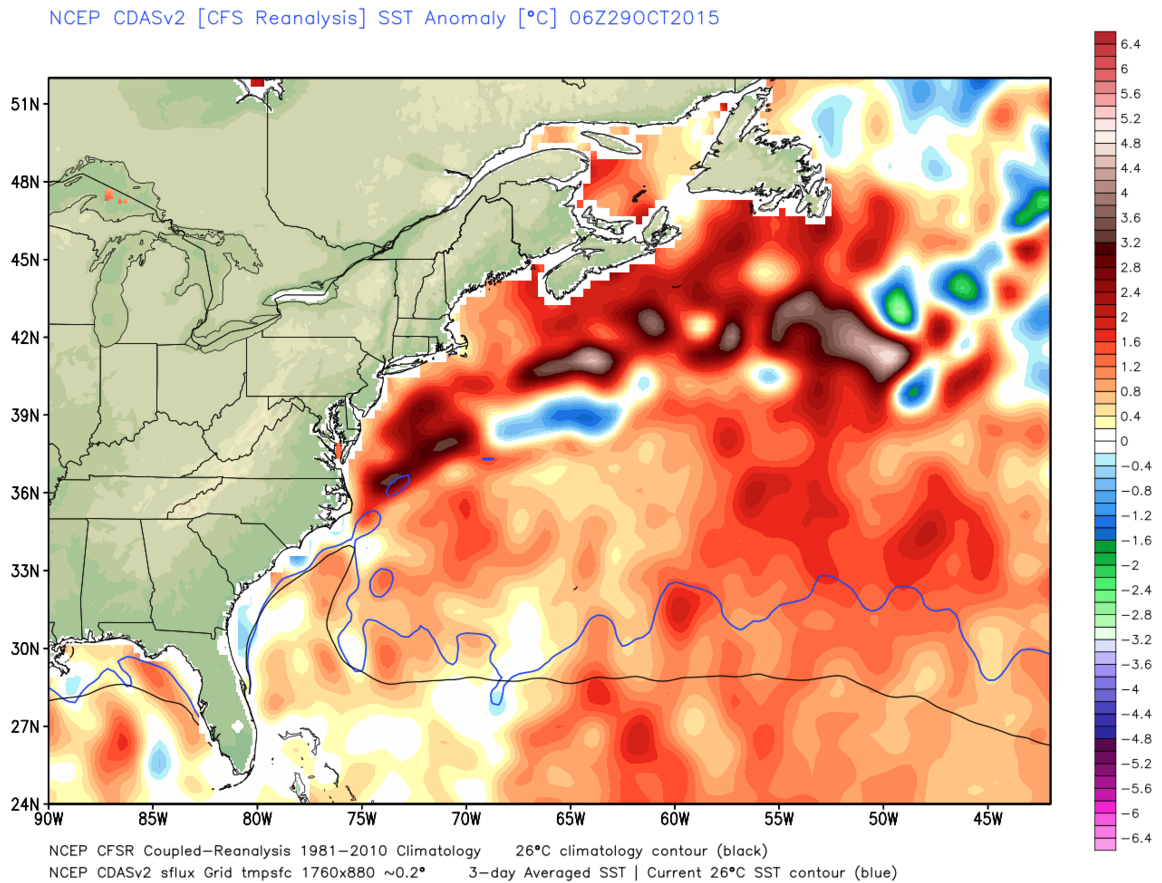

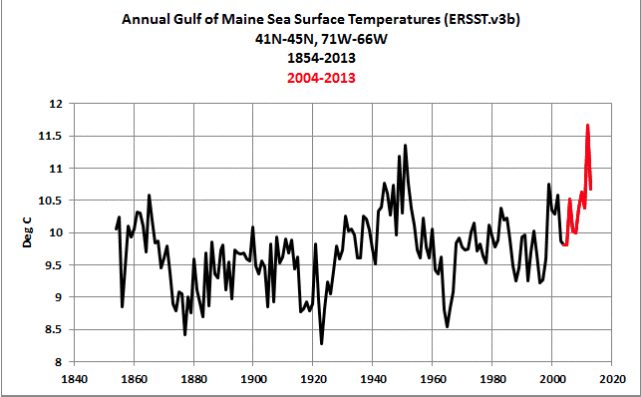

The other cause for the warming of the Gulf of Maine is the altering of the ocean currents in the area. Two underwater islands (Georges Bank and Browns Bank), hidden 40 feet below the ocean’s surface, block the entrance of the Gulf of Maine. Normally, the Northeast Channel that separates the two banks allows cold water that has entered the Gulf of Maine from the Labrador Current to exit back into the open Atlantic, allowing a gyre of nutrient rich cold water to circulate around the whole gulf. This gyre sustains most of the life in the Gulf of Maine, allowing it to be one of the most productive places for sea life in the North Atlantic. Recently, there has been much less cold water coming from the Labrador Current and more water coming through the Northeast Channel. Scientists suspect the rapid melting of the Greenland ice sheet is to blame. By cooling the Labrador Sea, the ice melt is disrupting the Labrador current, making it weaker and allowing warmer currents to enter the Gulf of Maine that would have been pushed out by the cold water. The change in currents has disrupted the Gulf of Maine gyre, resulting in less nutrient cycling and productivity, while at the same time causing water temperatures to warm up rapidly. The warming water and loss of nutrients for primary producers has resulted in unfavorable conditions for Atlantic cod. The shift in ocean currents is the main reason why the Gulf of Maine has warmed faster than 99 percent of the world’s oceans in the last century. In the last decade alone, Gulf of Maine ocean temperatures have increased by almost 4 degrees Fahrenheit.

Rapid warming in the last decade (in red) from a shift in ocean currents is suspected as the main cause for the lack of rebound in the GOM’s cod fish population.

In 2012, the Gulf of Maine saw its warmest waters in 150 years of recorded history. In these conditions, Atlantic cod are not able to rebound from overfishing. Being cold blooded, cod metabolism and behavior is directly linked to the temperature of their surroundings. Increasing the temperature a few degrees disrupts their eating patterns, reproductive cycle, their metabolic rate, where they swim, and how resilient they are to other changes. Also, it effects the other animals in the Gulf. Cod have a high trophic level, meaning they are near the top of the food chain. The effects of the decline of species lower on the food chain will trickle up to effect Atlantic cod. Also, cold-intolerant, invasive species have moved into the Gulf of Maine due to the warmer conditions and are also messing with the Atlantic cod’s food chain. The invasive green crab has been responsible for the decline of mussel and soft-shell clam populations in the Gulf, both of which cod eat.

The future of the Gulf of Maine’s Atlantic cod fishery may rely on more than just the lowering of cod fishings quotas. The environment of the Gulf is changing rapidly, turning it into a place that is less hospitable to Cod. Stopping the warming of the Gulf would require stopping the warming of the globe, which would require worldwide cooperation in the reduction of fossil fuel emissions, among other things. Also, a reduction in the fishing of other species in the cod’s food web, such as lobster, clams, herring, and mackerel would also help with the stressed cod fishery.

Sources:

Portland Press Herald, GOMA, Gulf of Maine Research Institute